Fighting Cognitive Debt in Agentic Code with Video Overviews

AI writes code faster than I can understand it — so now the system generates narrated videos of itself.

I've always been fascinated by synthesizers — the idea that you can generate sound purely from instructions, that a sawtooth wave can be expressed as a formula and a filter is a piece of math, reshaping it in real time. Building a software synth from scratch seemed an impossible task, until Claude Code came along. You can just throw half-formed ideas at it, and get something that works in a few hours; a working polyphonic synth plugin in C++20. However, since I didn't write any of the code, I'm missing the crucial part: understanding what exactly was implemented.

Researcher Margaret-Anne Storey calls this "cognitive debt": gaps in human comprehension that widen even when the code itself is perfectly fine. She observed coders becoming paralyzed not because anything was broken, but because nobody could hold a complete mental model of their own project anymore. Agentic coding amplifies this issue. The code arrives faster than your ability to absorb it.

Sure, I could go through the code and try reading bits of it, but that's not the same as writing and understanding the code. So I tried something different: what if the synth code also generates narrated video walkthroughs that explain it? Remotion is awesome for this, it even has agent skills so coding agents know exactly how to use the tool. And with custom narration using ElevenLabs to generate the voice-over, the whole thing feels as a natural YouTube series.

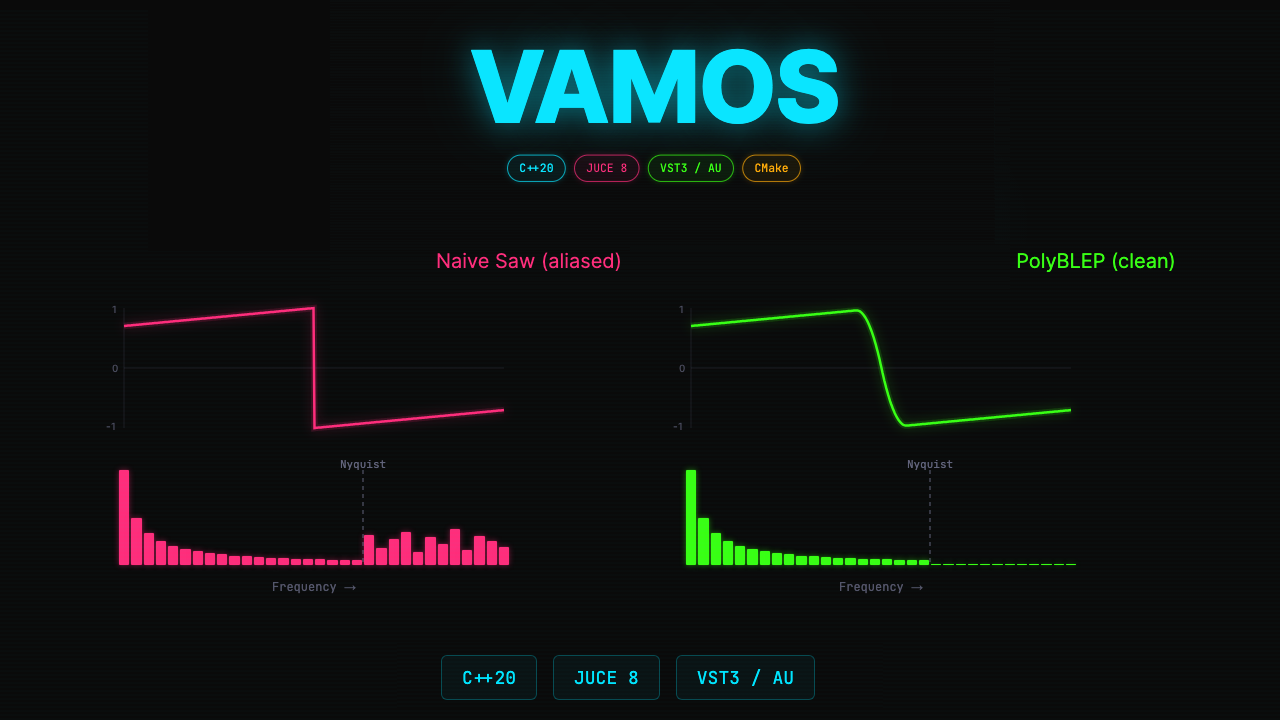

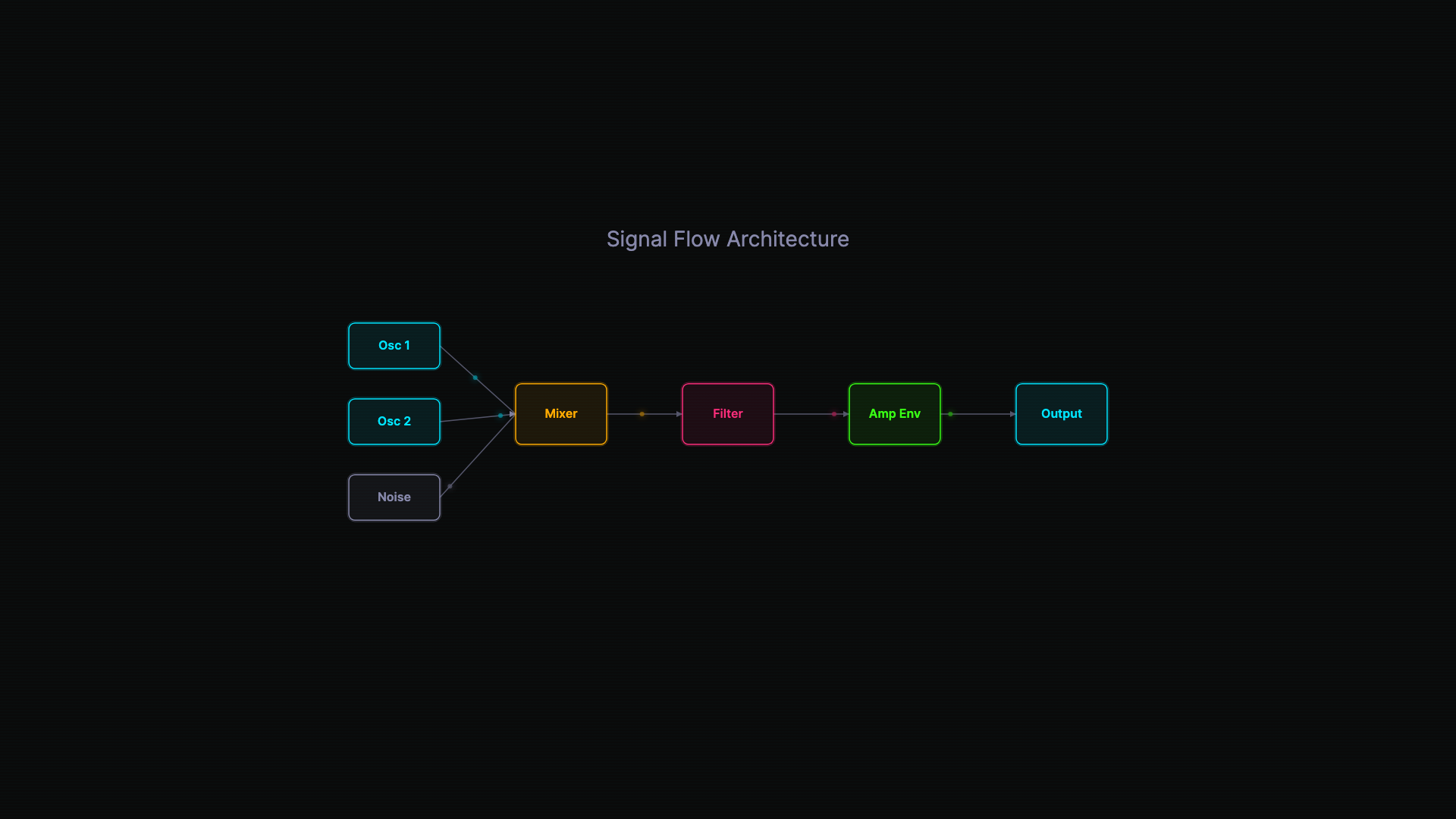

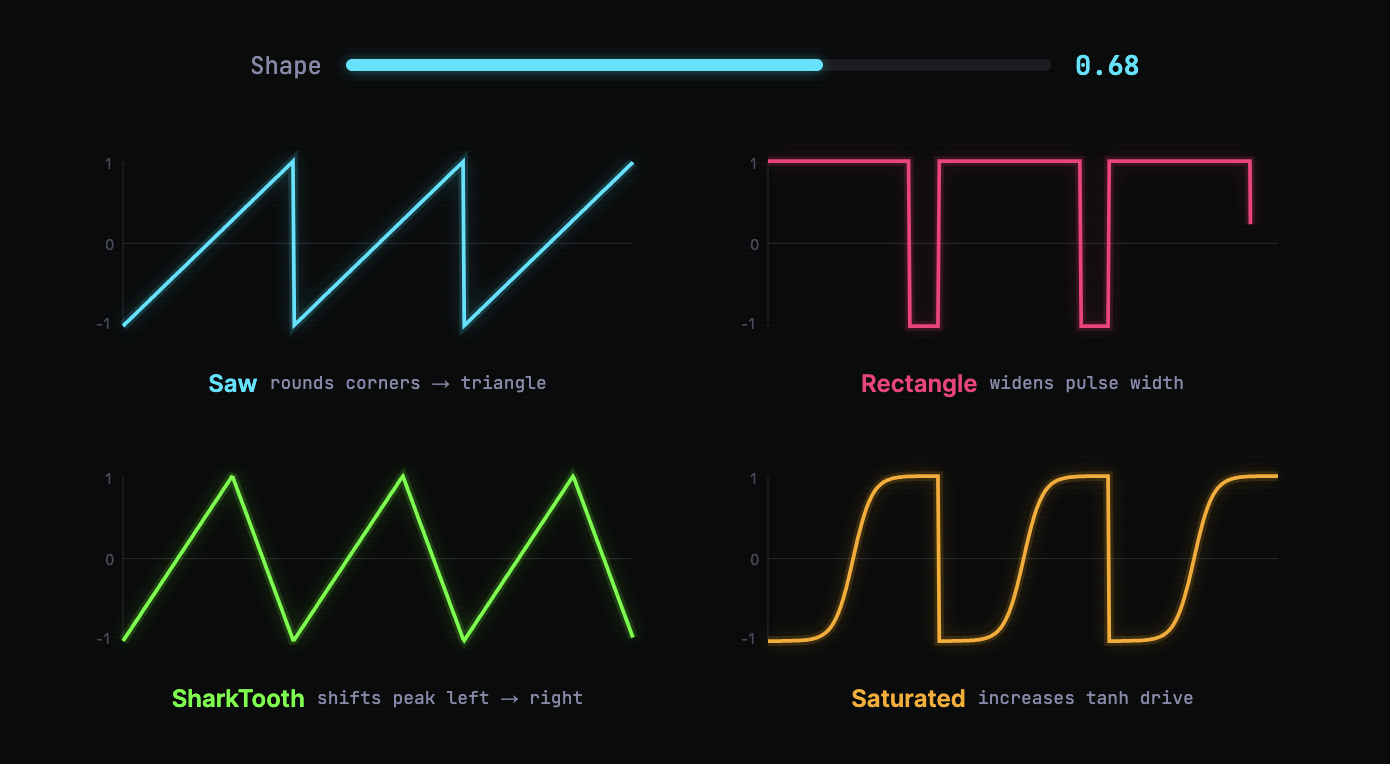

This could apply to any codebase, but I created Vamos, a polyphonic synthesizer, based on Ableton's Drift synthesizer. The synth has a standard signal path taking two oscillators and a noise source through a mixer, then a filter, then an envelope. A modulation matrix allows parameter automation. The synth is written in C++20 with JUCE.

Here's the first episode — an 8-minute walkthrough of Phase 1, from an empty project to a working eight-voice polyphonic synth:

The value of a concrete project

The synth gives the videos something real to explain — actual DSP code that runs in a DAW, not a toy example. The synth was deliberately built in pahses; docs/ capture the thinking behind each step, and that thinking becomes each episode's narration backbone.

The video pipeline

The videos are built with Remotion, a React framework for programmatic video. Each visual element — code blocks, waveform visualizers, architecture diagrams — is a component that animates based on frame count. Each episode is a directory of scenes, with a narration file, timing constants, and code snippets kept separate from the visual components.

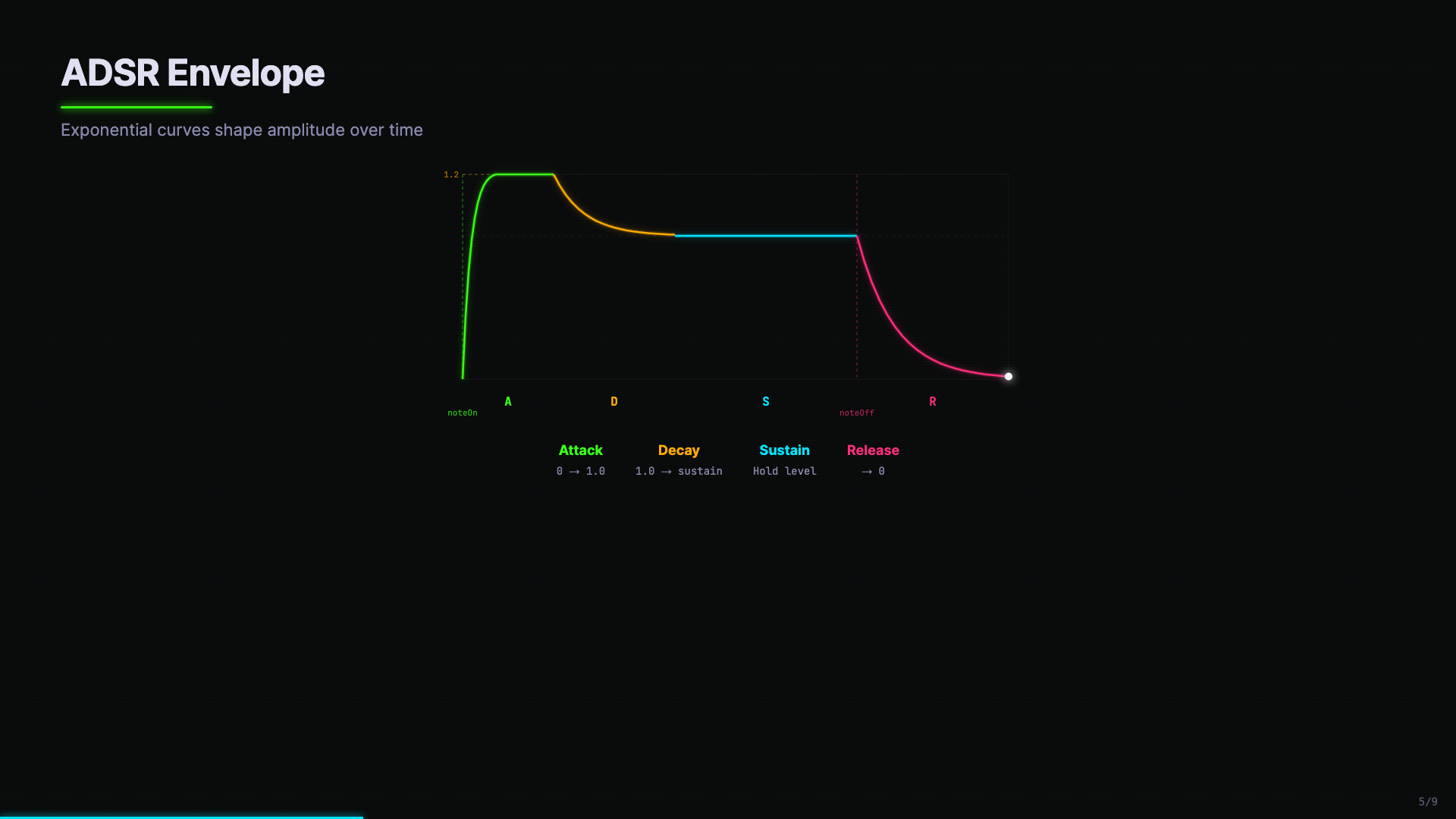

What's nice is that we can create domain-specific visualizations. Here I'm visualizing an ADSR envelope, color-coded by the phase (green for attack, amber for decay, cyan for sustain, pink for release), with the "overshoot line" (explained in the video!) clearly marked:

The production workflow has a deliberate two-pass structure. First, you iterate on the visuals without generation audio (which requires credits to generate). Then, the voice-over audio drives the final timing.

Pass 1: Structure and mute review. I ask Claude Code to outline the episode — what concepts to cover, in what order, and what visualizations would make each one click. That outline becomes a scene plan: each scene covers one topic with 2–4 sections that show different visual content sequentially. Claude Code writes the narration transcript and builds the Remotion scenes, but doesn't generate audio yet. Instead, it renders a mute video with burned-in captions. I review the video, without spending credits on text-to-speech. This loop — I give feedback, Claude Code adjusts text and visuals, re-renders — is where most of the iteration happens.

Pass 2: Voiceover and retiming. Once the "mute" video looks right, Claude Code generates voiceover audio through ElevenLabs. The generated audio durations then dictate the final timing: each narration segment's length in seconds gets converted to frames, and the scene durations are recalculated to match.

A subtlety with ElevenLabs: since each narration segment is a separate API call, the quality of the voice can drift between segments. The generation script handles this by passing adjacent segment text as context (previous_text / next_text) and chaining request IDs, so each segment is conditioned on the actual audio of the one before it.

Why video, not code

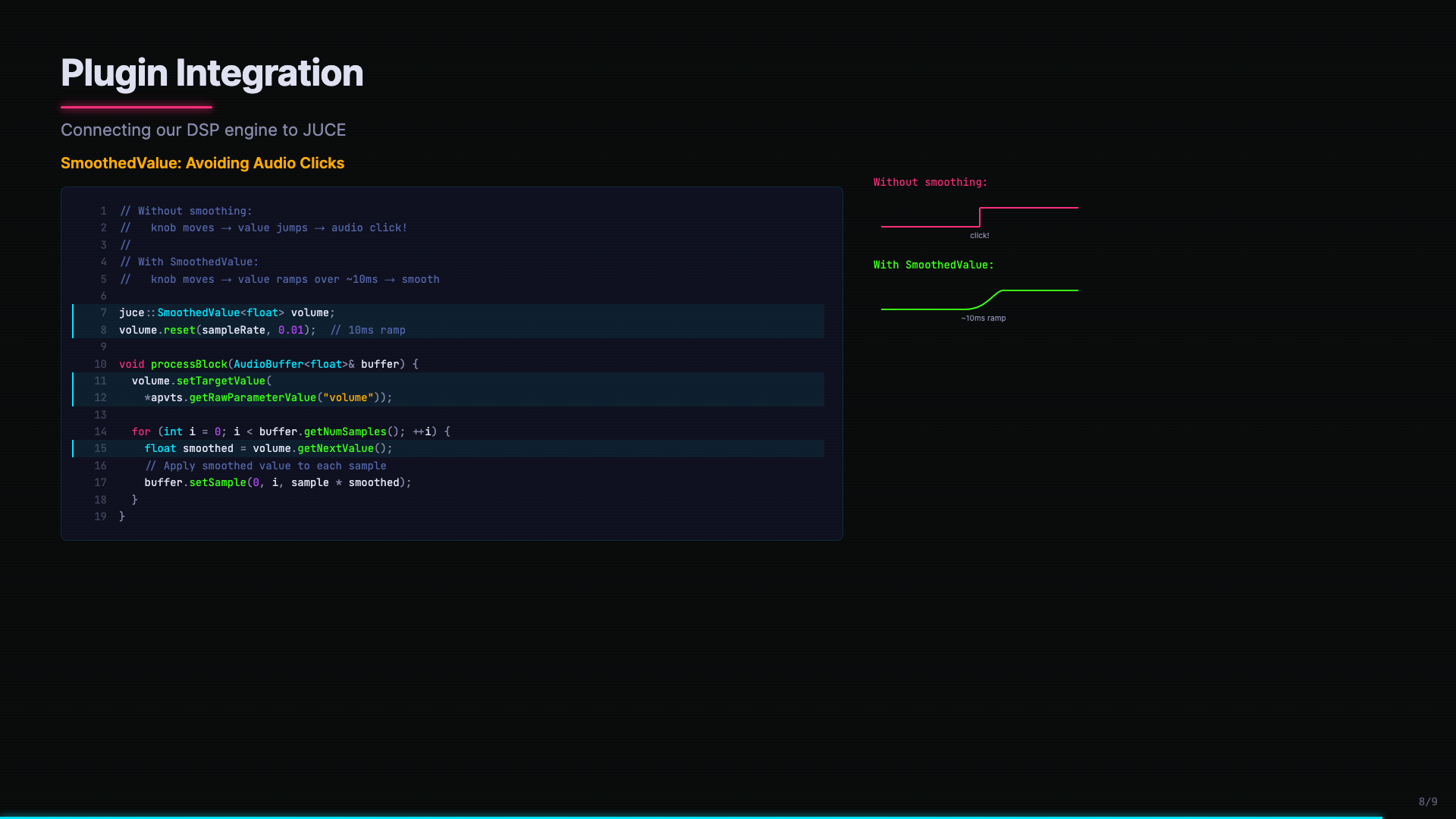

Using video, we can use other methods of explanation that code or comments can do: we can use metaphors, parts of the code, custom visuals, written explanations, ... This multi-modal way of explaining makes sure things stick. When the SmoothedValue code appears alongside a before/after waveform comparison — the click artifact versus the smooth ramp — you see why it matters, not just read about it:

Where this could go

I see three levels of video overview worth exploring:

"In the weeds" — PR-level explanations. You open a pull request, and a two-minute narrated video walks the reviewer through the changes, highlighting the important diffs and explaining the reasoning.

"Diving back in" — You took a vacation, or switched to another project for two weeks. You hit a button, and a just-in-time video catches you up on what happened while you were away.

"Archaeology" — Historical deep dives. How did the filter architecture evolve from a simple lowpass to eight filter types? Why does the envelope overshoot? These videos capture the reasoning behind decisions — the part that's hardest to recover from code alone.

The Remotion component library would grow over time — CodeBlock, WaveformVisualizer, SpectrumVisualizer, ADSRVisualizer, SignalFlowDiagram are just the starting set for audio projects. A web project might add APIFlowDiagram, ComponentTree, StateChart. Each domain builds its own visual vocabulary.

We're all figuring things out

So should we all be generating video? While this has been a useful trick, I don't think it's where we'll end up. Simon Willison has been playing around with the idea of a web comic to explain recent changes to a project, and that is another interesting idea.

The scaffolding is there, though. A narration-driven explanation system could work quite well, and is not specific to any particular type of code. The pattern of rough structure → fine-grained scene plan → transcript → mute review → TTS + retiming works quite well.

Keeping the system in your head

Margaret-Anne Storey's research shows that what differentiates effective teams is whether the humans maintain a shared "theory of the system." They know not just what the code does, but why it's shaped the way it is.

Video overviews don't eliminate cognitive debt, but can help rebuild shared understanding at a higher "bandwidth" than reading code line by line. When AI agents are writing most of the code, we need tools that help humans keep up. Maybe not at the code level, but at least at the comprehension level.

The code has become easy. Understanding is the hard part.